Preface. From the mines to the military.

Lester Joins The Fight.

Naples, Salerno and Mount Rotundo.

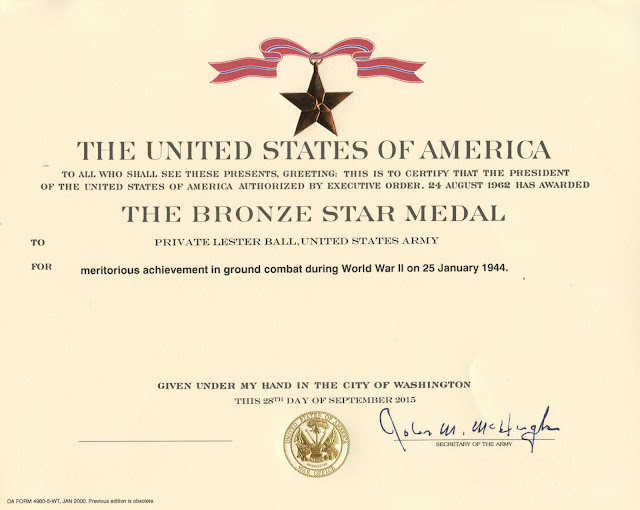

European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal.

After the fall of Sicily in August, the 30th Infantry Regiment was sent back to Marsala (on the west coast of Sicily). Their primary assignment was to guard the airport, but in reality the purpose was to wait until complete Italian invasion plans were developed at headquarters. One of the traveling USO shows starring Bob Hope and Frances Langford performed at the Trapani Bowl for the 3rd Division. General George S. Patton, Jr. also addressed the army during the event, “praising every unit and lauding the Division as a whole, as the finest infantry division any commander could desire.”

Naples harbor was full of sunken and burned-out ships. A wooden walkway was built across their decks for unloading men and supplies. Lester finally stepped ashore at the European Theatre to a battered and sick Naples, Italy on November 4, 1943. The city was in the midst of a typhoid epidemic.

Lester was expedited to the front, as extensive fighting in the hills to the north was intensifying. He joined Company A, 30th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Infantry Division near Rocca Pippirozzi (north of the town of Mignano) in the midst of its first major continental offensive (Operation Avalanche) in the Apennine Mountains.

Allied forces had made progress, pushing north through Formicola and the town of Cannavinelle (with Company A capturing Hill 689). Then, German defenses stiffened in the mountains and the conflict descended into a stand-off. At 0845 on November 8, the 30th Infantry Regiment (2nd and 3rd Battalions) launched a coordinated attack with the 15th IR along the southern slope of Mount Rotundo. Lester's company was instructed to hold its ground along Cannavinelle Ridge. For the next ten days, in freezing snow and sleet, the 1st Battalion was subjected to withering artillery fire from German positions atop Rotundo and Lungo. The most bitter fighting erupted on the night of November 7, when the Germans mounted a major counterattack upon Cannavinelle Hill ... earning it the name "Counterattack Corner." Again, on the 8th, three counterattacks were attempted, all coming from San Pietro-Venafro Road. The final attack of the day was only subdued when a mule train bringing badly needed ammunition arrived at the front with only minutes to spare.

Bad news from back home. Lester's oldest brother, Raymond, died having contracted tuberculosis while serving with an army medical detachment. He was honorably discharged in May, when he was diagnosed, and transferred to the Veteran's Administration hospital in Oteen, North Carolina where he received care for six months.

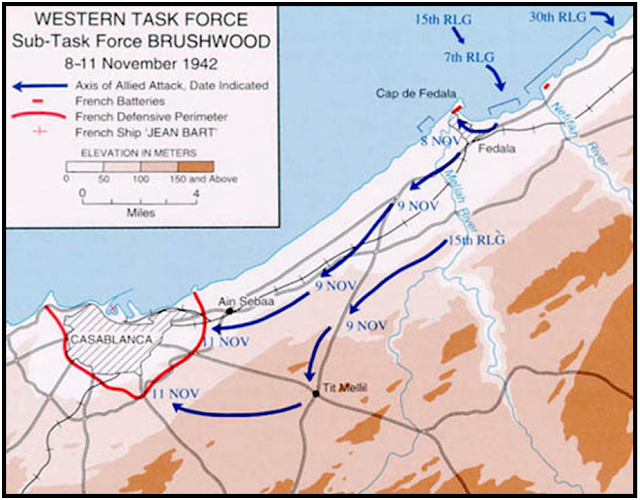

While Lester was enduring this concentrated ground-training, the military brain-trust was finalizing plans for a high-risk surprise attack.

In December, while recovering from pneumonia in Marrakesh, Winston Churchill devised a plan to land two divisions at Anzio and launch an end-run attack, behind the German forces, and take Rome. 3rd Infantry Division General Truscott strongly opposed it, saying that it would be a “suicide” mission and that there would be no survivors. General Clark concurred with this assessment and canceled the operation. Winston Churchill appealed to President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the plan was reinstated under the name of Operation Shingle.

After some initial difficulty transporting supplies and maneuvering vehicles (Sherman tanks and M-10 tank destroyers) Company A spearheaded the action, crossing the West Branch Creek at 1000 and progressing on a house-by-house basis. However, during the night, German General Alfred Schlemm of the Wehrmacht had fortified his assets, bringing in anti-tank cannons and large-caliber machine gun emplacements. In addition, five more divisions were on their way from Rome.

Only later would it become known that the Germans had been intercepting allied radio communications and knew extensive details about Operation Shingle. They were far more prepared for the assault than the allies anticipated. The 'wildcat' that Churchill had hoped to unleash upon the enemy had become a 'beached whale'.

Actress Marlene Dietrich visiting the 300th General Hospital

On June 20, Lester returned to Mad di Quarto, for additional intensive large-scale amphibious training. Emphasis was placed on five-mile conditioning marches and beach assault practice. The 30th IR was soon ready for its next great conquest, the French Riviera.

The Battle of Anzio is considered one of the most important and brutal battles in the history of mankind. More than twelve thousand soldiers were killed in action, and sixty-seven thousand were wounded in the four-month-long conflict. In hindsight, most military historians acknowledge a multitude of strategic and tactical blunders that made the struggle horrendously arduous and required great fortitude and often, heroic action, on the part of the soldiers ... like those of Pfc. John C Squires, 2nd Leutenant Randolph Bracey, and Sgt. John W. Dutko, all of Lester's Company A, who gave their lives and earned high military honors at Anzio.

Bronze Arrowhead (for amphibious landing).

Assigned the mission of reducing the giant Citadel fortress, key defense bastion of Besancon, and clearing the enemy from vital southern industrial section of that important road net center, the 1st Battalion jumped off on a night frontal attack. Pushing forward aggressively against dogged German resistance, the 1st Battalion climbed slippery hills through pouring rain under murderous, grazing machine gun, machine pistol, mortar, and flak wagon fire to assault and destroy strong enemy forces entrenched in three rock-walled, supposedly impregnable forts situated on high ground commanding all approaches to the bottle-necked Doubs River loop section of the city. One by one, the battalion reduced two lesser forts and finally the mighty Citadel, employing skillful flanking maneuvers and masterfully coordinating the heavy fires of infantry-supporting weapons and those of attached armor and artillery. Although it had moved hundreds of miles and fought two major engagements during the preceding twenty-two days and although it had been moving thirty-six hours without rest prior to launching the twenty-two hour attack, the 1st Battalion with aggressive, inspired leadership and outstanding individual heroism overcame all opposition and seized its objectives. A fresh, reinforced enemy battalion was wiped out, 50 Germans killed, 70 wounded, 328 enlisted men and eight officers captured, and vast quantities of German material, including enough mortars, machine guns, rifles, and pistols to equip a battalion were seized or destroyed during the brilliant action. The 1st battalion's spectacular achievement frustrated the German intention to hold the Citadel until 15 September, pierced the heart of the enemy's defenses of Besancon, crumbling their entire system of mutually supporting forts, materially assisting the 3rd Infantry Division in blocking a vital escape route to German units trapped in the west, and speeded pursuit of remnants of the battered German Nineteenth Army fleeing to the Belfort Gap. The heroic performance of the officers and men of the 1st Battalion, 30th Infantry Regiment reflects the finest traditions of the Army of the United States.By order of the Secretary of War.G. C. Marshall, Chief of Staff.

To force a crossing of the Fecht River in its zone, advance with all possible speed to clear the east-west road in its zone through Colmar Forest (Foret Communale de Colmar), and seize objectives indicated on the III River. To force a crossing of the III River at the earliest possible moment and continue the advance to seize objectives indicated (along a line running east from the III River south of Maison Rouge bridge).To extend south to another phase line, blocking to the east. On Division order, to be prepared to regroup in the Horbourg-Bennwihr area prepared to execute maneuver and capture Colmar from the east, or to pass to Division reserve. In addition, 30th Infantry was to protect its own left throughout the advance south along the east side of the III; to protect the Division left; to maintain contact with 1 DMI and 5 DB on the left flank, and to reinforce its supporting engineers with one rifle company from the regiment's reserve battalion for the purpose of carrying an infantry footbridge from the Fecht River to the Ill.

Fighting incessantly, from 22 January to 6 February 1945, in heavy snow storms, through enemy-infested marshes and woods, and over a flat plain criss-crossed by numerous small canals, irrigation ditches, and unfordable streams, terrain ideally suited to the defense, breached the German wall on the northern perimeter of the Colmar bridgehead and drove forward to isolate Colmar from the Rhine. Crossing the Fecht River from Guemar, Alsace, by stealth during the late hours of darkness of 22 January, the assault elements fought their way forward against mounting resistance.Reaching the Ill River, a bridge was thrown across but collapsed before armor could pass to the support of two battalions of the 30th Infantry on the far side. Isolated and attacked by a full German Panzer brigade, outnumbered and out-gunned, these valiant troops were forced back yard by yard. Wave after wave of armor and infantry was hurled against them but despite hopeless odds the regiment was hurled against them but despite hopeless odds the regiment hold tenaciously to its bridgehead. Driving forward in knee-deep snow, which masked acres of densely sown mines, the 3d Infantry Division fought from house to house and street to street in the fortress towns of the Alsatian Plain.Under furious concentrations of supporting fire, assault troops crossed the Colmar Canal in rubber boats during the night of 29 January. Driving relentlessly forward, six towns were captured within 8 hour hours, 500 casualties inflicted on the enemy during the day, and large quantities of booty seized. Slashing through to the Rhone-Rhine Canal, the garrison at Colmar was cut off and the fall of the city assured. Shifting the direction of attack, the division moved south between the Rhone-Rhine Canal and the Rhine toward Neuf Brisach and the Brisach Bridge. Synchronizing the attacks, the bridge was seized and Neuf Brisach captured by crossing the protecting moat and scaling the medieval walls by ladder.In one of the hardest fought and bloodiest campaigns of the war, the 3d Infantry Division annihilated three enemy divisions, partially destroyed three others, captured over 4,000 prisoners, and inflicted more than 7,500 casualties on the enemy.

The jump off took place on March 15, 1945. The movement of the 30th Infantry Regiment from Nancy would be one of secrecy, all markings for the units in the main assault would be blackened out using adhesive. Numbers, patches both on the shoulder and on the helmet were completely removed. The pace of attack was slow at first, while Lester and Company A led the regiment across the mine-filled Siegfried Line. He was among the first handful of Allied troops to cross that infamous line.

The 3rd Division's crossing of the Main River was accomplished by the 30th Infantry taking the lead in assault boats at a point near Untertheres. Company A, commanded by Capt. Hugh S. Montgomery, met enemy Flakwagon and other fire near the village of Dampfach shortly after making the crossing but allied artillery placed effective fire on the enemy positions and silenced the only display of resistance that marked the crossing.

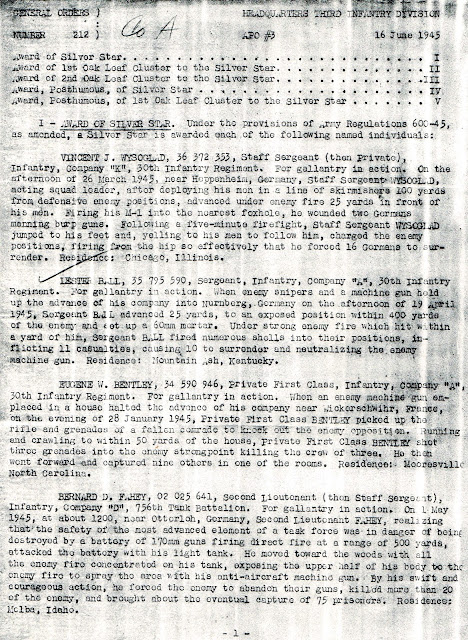

Lester grabbed a 60mm mortar and ran twenty-five yards clear of his men. Disregarding his own life and completely exposed to enemy fire, he set up the weapon and began firing on the Nazi positions. Rockets exploded on the ground at his feet, covering him in dirt and ripping his arms, legs, and back with shrapnel. Bullets ricocheted all around him. He fired several rounds, one of them making a direct hit on the gunners, killing several and incapacitating eleven of them. As a result of his actions, ten Nazis surrendered and he and the two remaining men in his squad survived.

Another member of Company A also performed heroically during that same engagement. Technician Fifth Grade, Courtland D. Mott, acted with gallantry and intrepidity in battle, and made the ultimate sacrifice for his fellow soldiers. He earned a posthumous Silver Star.

mounted atop the stadium structure.

Good Conduct Medal.

World War II Victory Medal.

Army of Occupation Medal (Germany clasp).

The 3rd Infantry Division, with the 30th Infantry Regiment in the lead, surged deeper into Bavaria, capturing Munich on April 30th. As Lester Ball was marching into Munich, Adolf Hitler was committing suicide in the Fuhrerbunker, three hundred miles to the north, in Berlin.

In a rare, post-war interview, German Field Marshall Kesselring was asked by Chicago Tribune war correspondent Seymour Korman, "What was the best American division faced by troops under your command on either the Italian or Western Fronts?"

Without hesitation, at the top of his list was, "The 3rd Infantry Division."

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Silver Star to Sergeant Lester Ball (ASN: 35795590), United States Army, for gallantry in action while serving with Company A, 30th Infantry Regiment, 3d Infantry Division. When enemy snipers and a machine gun held up the advance of his company into Nurnberg, Germany, on the afternoon of 19 April 1945, Sergeant Ball advanced 25 yards, to an exposed position within 400 yards of the enemy and set up a 60-mm. mortar. Under strong enemy fire which hit within a yard of him, Sergeant Ball fired numerous shells into their positions, inflicting eleven casualties, causing ten to surrender and neutralizing the enemy machine gun.General Orders: Headquarters, 3d Infantry Division, General Orders No. 212 (June 16, 1945)

Lester departed the European Theatre (Marseille, France) on October 23, 1945, arriving in CONUS (New York City) on November 2, 1945. He returned among a fleet of fourteen ships, carrying 15,522 soldiers. The convoy slipped into New York Harbor as a dense fog was lifting to reveal the Statue of Liberty in all her glory. He clambered down a cargo net (for the last time) onto a barge that took him up the Hudson River to Camp Shanks, where he overnighted before taking a train homeward.

Lester was honorably discharged from active duty at Camp Atterbury, Indiana on November 7, 1945. At the time of his discharge, his organization was listed as Headquarters Battery, 965th Field Artillery Battalion (155mm Howitzer), VII US Corps. He had completed two years, six months, and thirteen days of active service (eighty percent of his service was involved in heavy combat). His mustering out pay was $300.

To be buried at Arlington National Cemetery is a tremendous honor. As a Silver Star recipient, Lester qualified for interment there, but the idea of not being near Edith made him hesitant. However, after discussing the matter with his family, and confirming that both he and Edith could be buried there together, he was convinced that it was important to accept the honor and leave a significant legacy for future generations.

Edith passed away in 2007 and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery. Lester attended the simple ceremony on a cold and blustery winter day, along with son Michael and daughter Tammy.

Edith passed away in 2007 and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery. Lester attended the simple ceremony on a cold and blustery winter day, along with son Michael and daughter Tammy. Barely a year later, Lester would join Edith. In June of 2008, after passing away on April 29th, Lester was buried at Arlington with military honors. A brief private ceremony took place under a small tent that included a twenty-one gun salute, the presentation of the flag, and the playing of taps. Then Michael and Tam carried his ashes from the funeral bier to the gravesite and placed them on the ground next to the white arched headstone marked with Edith’s name. The headstone would be later removed and re-carved with his name and military citations. From his location in Section 54, surrounded by other men of valor, the Washington Monument is clearly visible.

A truly beautiful man.

Bonner: Certainly, sir. Service-connection for a hearing loss is the issue that we are now contending. The Veteran is present today to present his testimony and contentions that service-connection for a hearing loss should be granted due to the wounds to his head and jaw in World War II. The Veteran also requests a copy of today’s Hearing transcripts. At this time, I have a few questions for Mr. Ball.

CHM: Alright, proceed Mr. Bonner.

Bonner: Mr. Ball, I’d like you to describe the incident where you received the injury to your jaw.

Lester Ball: This was on the Anzio Beachhead. And we were told to attack this position and take two (2) houses and take a big ravine, which we did. And with all the artillery and the mortars and “88s” and everything coming in, that’s when a shell got me through the chin. And then I went back to First Aid, which I was out for about a month, then I went back up which represented about six (6) months altogether on the Anzio Beachhead.

Bonner: Okay. Now when you were back having your jaw worked on, how was your hearing at the time?

Lester Ball: Well, when I got hit and I went back, we had a Field Hospital there. And I went in, which they done my wound and everything. And then they shipped me out of there by boat to the 300 General Hospital, and my … that’s when they wired my teeth together and put my whole chin in … and I couldn’t talk. I couldn’t hear anything for several days until they took the wires off of my mouth and opened my mouth up, my hearing was starting to come back, which was it was like my whole head was plugged up at the time.

Bonner: Yes.

Lester Ball: And that was some terrible feeling, some experience to go through that. Felt like I was going to lose my sanity.

Bonner: You say you also received a couple of other wounds that weren’t in your record. You have one (1) scar on your … the left side of your skull. Could you display that to the Hearing Officer, please, as to where it is located?

Lester Ball: This was from D-Day in Southern France, we was going up through France. And I got hit in the back of my helmet which made a dent in it, which I was left with a big knot on my head. And I went back to First Aid, which they operated on me and, you know, put stitching on it. And then I went back into battle again.

Bonner: How long were you back getting that treated?

Lester Ball: Just long enough to get the …

Bonner: A week or so?

Lester Ball: Yeah, it wasn’t very long until they took the stitches out. Maybe eight (8) days or something. Didn’t take too long.

Bonner: You also received the wounds here, back where you … where eventually a piece of shrapnel worked out and was removed by your private physician. That also isn’t part of your record. Would you just talk about that a little bit?

Lester Ball: Well, I had this piece of shrapnel on my spine which they said would work out, which it did years later.

Bonner: About how long was that?

Lester Ball: Oh, about 1960, I believe. It worked up to where it was … where it would come right out. My doctor then took that out.

Bonner: So, all in all, you were wounded three (3) times, at least once what would be considered a severe wound. Would … was this a kind … I mean, the number of battles you were in, you were with your outfit from when they landed in Africa, all the way to Austria.

Lester Ball: I was with my outfit from Italy all the way into Germany.

Bonner: Okay. And you said it was for two (2) years?

Lester Ball: Two years. I was in battle for most of the time for the whole two years, all the way from Anzio Beachhead all the way into Germany.

Bonner: That’s where you got your Silver Star?

Lester Ball: I got my Silver Star in Salzburg (incorrect) … well, just after the Siegfried Line. We went through the Siegfried Line and they had us pinned down, this machine gun did. And my sergeant asked me to bring … and it was only … he had only me and two other guys left in my Squad. And he asked me to bring a mortar and come up, so I set the mortar up and got real lucky on the first barrage, it hit the machine gun. Then I laid down three (3) or four (4) more rounds with the mortar, which they run up the white flag and gave up. So my sergeant congratulated me. And that’s the reason I got a Silver Star. He turned my name in and made a claim, and they gave me a Silver Star for that.

Bonner: You say you were in a tremendous amount of combat. You said you had artillery barrages, you had 88-millimeteres, from railroad guns …

Lester Ball: Ack-ack …

Bonner: Mortars …

Lester Ball: … mortars …

Bonner: … machine guns …

Lester Ball: … tanks and machine guns. You name it, I’ve had it.

Bonner: How close were you to your own guns when they were fired?

Lester Ball: Well, when I first went into Anzio Beachhead, I was a rifleryman. And I got one Division that went back in Anzio Beachhead before we … had made the sale made then with Kruschev. They touched me, they gave me a sergeant’s rating and gave me a platoon, a mortar platoon, which with shooting got damage all the time, ‘cause if you drop a shell into it, it explodes. And there was no way to protect you from the noise of firing a mortar. And that’s what I set up and blasted this machine gun.

Bonner: How many days would you say you were actually in battle, when all these enormous explosions and concussions were about you? How many actual days?

Lester Ball: I would have no idea.

Bonner: But it was fairly continuous?

Lester Ball: On Anzio Beachhead, that was six months down there, that was from January ‘til June which, if you’re on Anzio Beachhead, that’s only about five to fifteen miles that were under continuous barrage. But you got so good at it, that you’d know a shell was comin’ at you, off to the side of you, over your head, you’d know where the shell was coming, when it was coming in. And you could hear them come up. And you could tell when they was gonna hit close to you. But those 88s, if you heard it you’re alright; if you didn’t it was too late.

Bonner: You’d rather hear ‘em coming, then. When did you first start noticing that your hearing was declining?

Lester Ball: Well, I noticed that after I got out of the service, when I’d try to talk on the phone or anything, I couldn’t hear in the one ear, so I’d switch to the other ear.

Bonner: Which ear was the one you couldn’t hear in first?

Lester Ball: My right ear.

Bonner: And why are you not wearing a hearing aid in there now? And do you have a hearing-aid in your left ear now?

Lester Ball: Well, the doctor explained to me that he thought a hearing-aid in my right ear, when I had so much nerve damage, that it would not do me any good. And so he put a hearing-aid in my left ear, my best ear. But then he tried to raise the volume where I could …

Bonner: And it would compensate for the hearing loss in your other ear?

Lester Ball: And that’s what he told me, but he told me he didn’t think it would do any good at all to put one in my right ear. But then I go to Gainesville and they think I should have …

Lester Ball: I was in a finishing company where we done all kinds of finish work, hanging silk-screen, polishing, plating … I was mostly in the paint area of the finishing company. It’s a nice quiet … not a lot of noises. But the company is so big now, they was like a family thing when I started. I worked there forty (40) years, and the company got so big and my hearing got so bad in the last ten years that they took me out, and I was computering loads on the big trucks, balancing the loads on the big trucks when they went out. For the past five years, that’s what I done. And computerized and balanced all those loads.

Bonner: Has any audiologist said that the reason your hearing has declined is because of the constant noise exposure during World War II?

Lester Ball: No, we had my hearing tests and all of that. I didn’t even pass when I first had it. There’s no one ever said they …

Bonner: Did you ever tell anyone about the noise exposure you had in World War II?

Lester Ball: I asked when I went down to Cincinnati to the Veterans Hospital down there, when I was down there on my jaw.

Bonner: When was that?

Lester Ball: That was about 1950, maybe 1955 or so … in the 1950s. And I asked them, but they said they didn’t want that, they wanted to take care of my jaw. So I didn’t get any information on my hearing or no information on my other wound on the back of my head or anything. The only thing they wanted to do was work on my chin. That’s the only thing I got done from them at all.

Bonner: Why have you waited so long to come in here?

Lester Ball: Well, I was in Cincinnati, they wanted to redo my whole chin, to re-operate. So I didn’t want that, so I left and I didn’t go back. I got my own doctor, a dentist who was taking care of my chin. He passed away. So I went back, got an appointment and went back down to see them to get my teeth and chin worked on by a dentist. They wanted to operate on me and everything, so they could take out all the scar tissue, but I thought that would be too hard, you know …

Bonner: Leave it like it is.

Lester Ball: … to leave it like it is.

Bonner: I have no further questions, Mr. Johnson.

CHM: Thank you, Mr. Bonner. Mr. Ball, while you were in the hospital being treated for the injuries to your jaw, did they ever give you any specific treatment for your ears?

Lester Ball: No.

CHM: Do you recall at the time while you were hospitalized, I know you stated that you could not hear for a while afterwards, did you notice or were you made aware of any bleeding from the ears at that point?

Lester Ball: I don’t think so.

CHM: Approximately after how long after you were aware of your injuries did your hearing begin to return?

Lester Ball: It was probably maybe seven (7) or eight (8) days, something like that … before my hearing started to clear up.

CHM: Did you, at any other point in time while you were still on active duty, seek any treatment for your ears?

Lester Ball: I never had them treated.

CHM: In your testimony you stated that you had a hearing test, you were not able to pass it. Where was this and what time-frame are we talking about?

Lester Ball: This was where I worked, some kind of survey or something, they was going to be giving hearing tests and stuff. The state of Ohio was running it. And they came in; I didn’t pass it when they gave it to me. And that was the first hearing test I ever had.

CHM: Do you recall the year when that happened?

Lester Ball: Probably the 1960s.

CHM: During the period you were in combat in Europe, I know that, the noises of artillery and the mortars, the small arms is a constant factor in combat. But were there any particular situations or times when you can remember that the blast or the percussion was so close to you that you could actually feel the percussion to your ears?

Lester Ball: You could feel the ground moving while you’re into it, you’re so close. There was a lot of it aimed directly at you. If an artillery shell made a five foot crater over here (five foot away from you) you could feel the whole thing. And when that railroad gun came out, that 282 or 280 or 283 or whatever it was, every time it came out and they’d drop one of theirs over to you, it really vibrated everything. And when I was back in the 300th General Hospital, even back there, they bombed that thing too. And had to do all kinds of duck and cover back there in the hospital. When we’d go through them artillery barrages, they were something else. You got good enough at it by going through so many of them that you could tell when the rounds were coming in or when they were going by. And you could duck down in your hole and protect yourself. And when you fired your mortar and every time it blasted, you could only hold one ear because you had to drop the shell with the other hand. And every time it went off, you got a blast in the ear from it.

CHM: Mr. Ball, following the injury you received to the jaw, were you given an option of returning stateside or remaining with your unit?

Lester Ball: Yeah, I could have stayed if I wanted to.

CHM: But I mean when you were in the hospital, were you given the option of returning stateside at that point in time?

Lester Ball: No. Never was.

CHM: Alright, thank you, Mr. Ball. I have no additional questions at this point. Mr. Bonner, do you have any additional questions of Mr. Ball?

Bonner: Not of Mr. Ball. I do have one question for Ms. Ball, if I may. Ms. Ball, how long have you known your husband?

Edith Ball: I met him just a couple months when he came out of the service.

Bonner: Did you notice any hearing problems at that time?

Edith Ball: We’ve lived through this for forty-four years.

Bonner: Did he ever complain about his ears over that time?

Edith Ball: Well, he was always conscious of his scars and he’s always been very quiet. He’s never talked a whole lot. I learned to recognize when something was really on his mind, and I would try to get him to talk about it. So a lot of things that he’s told me, he’s brought out like that. But he’s complained with his … with his ears … with his whole head. The pressure would be so bad in his head. You’ve seen how he puts things off, no one could ever get him to go. He won’t apply for help.

Bonner: Well, we will try to address this. That’s why I had this testimony.

CHM: Any final comments?

Lester Ball: I … well, I would like to make a comment. I do need help with my hearing. And I don’t have enough money; I only get a small allotment to live off of and it takes most of it for me to live. And I don’t have the money to pursue this myself. That’s the reason I am here, trying to get some kind of help so I’ll be able to hear even with any type of hearing-aid. If I can get the person on the good side and I have to hear them, they’re dim. I can understand most of what they saying if I look straight at them, which I have gotten very good at that because of my hearing. I don’t know what else to say. I do need help.

CHM: Mr. Bonner, is there any additional?

Bonner: May I comment. One of the things by examining the record, we notice a few of the problems that were exhibited today. And the primary one is … the fact that I believe my client suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder, and we will be amending his claim for that. The thing that seems to occur is essentially his avoidance of having sought help immediate after service for his problem. Apparently it is involved with his nervous condition; and what we would like to do is have an assessment made under that premise, in that he … there was an avoidance … to a problem so severe at the time. But this nerve damage is exhibited in the report made by the people in Gainesville; what they said is, lots and lots of nerve damage. And he has no other scars than that which he received in the service, he had no severe noise exposure beyond what he had in service, which was two (2) years of constant combat, active combat, front-line, heavy-duty, us-against-the-Germans. And I’d like that to be really appreciated by yourself and whoever else would have to review this.

CHM: Thank you, Mr. Bonner. You will be submitting the Amended Claim. Then it is noted on the transcript that it would be best to also get written documentation in the file for the amended issue. I would like to thank you, Mr. Ball, for appearing and presenting your testimony, and I’d like to thank you, Ms. Ball, for appearing and testifying also, and Mr. Bonner for his able representation. We will be adjourned.

(9:30am)

and photography used in this account.

.jpg)

.jpg)